American Hegemony - Friend Or Foe?

Is the United State's dominance of global security a force for world peace or an enforcement of oppression?

By Matthew Ssali | 24 June 2025

If you live in the Western world, your standard of living is likely underwritten by an unspoken truth: the Pax Americana. Since the conclusion of the Second World War, and more firmly after the Cold War ended in 1991, the United States has functioned as the de facto stabiliser of the global order. Its economic clout, military dominance, and cultural saturation have propped up a system that, for all its flaws, has kept globalised trade, relative peace between major powers, and liberal values in motion.

But is this dominance justified? Or, as critics argue, is it merely a masked imperialism that sows chaos for profit? In the spirit of inquiry, and from the vantage point of a British observer, this article explores the modern relevance of American hegemony, especially amid a world riddled with renewed threats, fractured alliances, and technological upheaval.

Stabilising the Global Economy

The most immediate benefit of American dominance is economic stability. The United States dollar is the world’s reserve currency, comprising around 88% of global forex trades, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Key commodities like oil, gas, and wheat are priced in dollars, giving investors and states a stable benchmark amid regional shocks. Recent geopolitical tension in the Strait of Hormuz—where 21% of global petroleum shipments pass—has reignited concerns. Iran, increasingly emboldened by a Russia-China-Iran axis and flush with support following the Gaza War escalation of 2024, continues to threaten shipping routes. As of June 2025, Houthi-aligned naval groups in the Red Sea have disrupted dozens of tankers, while Tehran flexes its regional leverage. A brief Iranian naval blockade in April 2025 caused only a temporary spike in oil prices, thanks to swift diplomatic and military responses led by the U.S. Fifth Fleet and CENTCOM.

Critics rightly point out that American dominance doesn't always prevent volatility. The Hormuz situation proves that even hegemonic systems have fault lines. When geopolitical actors respond to perceived U.S. weakness—or excessive aggression—markets suffer. The interconnectedness of the system becomes a liability. If this is true, then logically, the price of oil should soon skyrocket.

Yet to accept this counterpoint is to ignore the alternative. The Middle East has no uncontested power. Were the U.S. to withdraw, the vacuum would invite regional factions—Sunni, Shia, nationalist, and radical—to seize dominance. They would wield oil as a strategic asset and extract concessions in a zero-sum environment. Prices wouldn’t just rise—they would become wildly unpredictable. American power, however flawed, acts as a governor on these ambitions.

Protecting Western Interests (Indirectly)

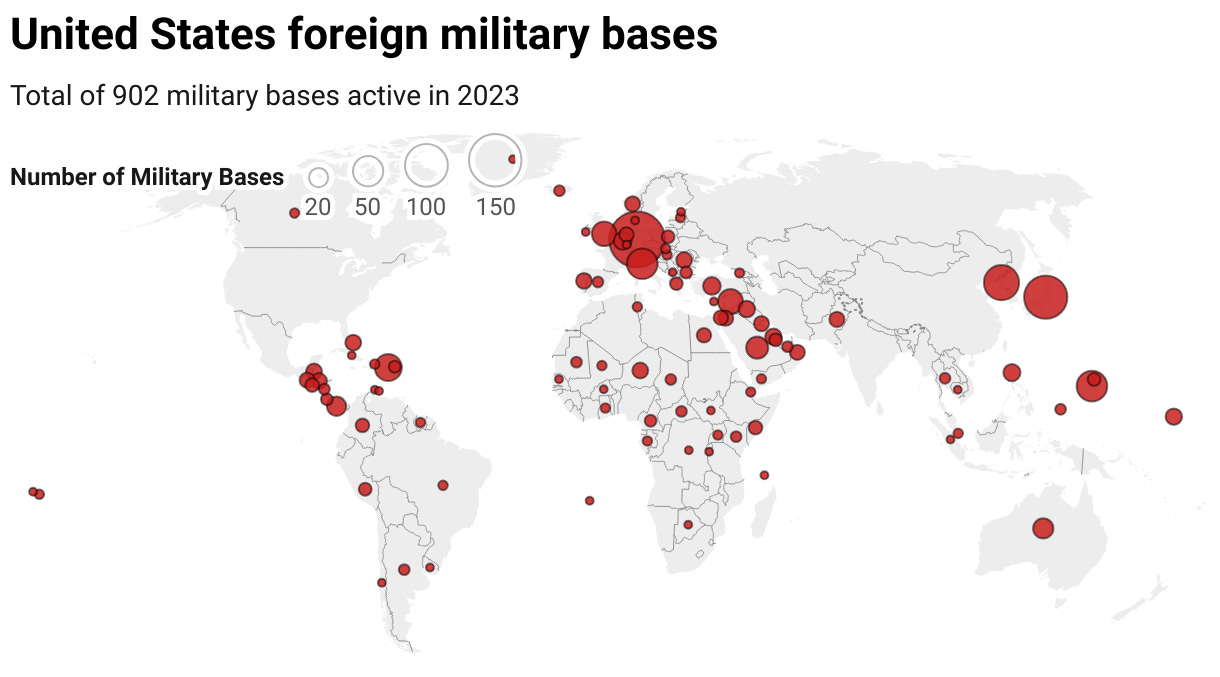

In theory, American military presence and diplomatic networks shield Western values—free markets, democracy, press freedom. Through NATO, intelligence sharing, and financial architecture like SWIFT, the U.S. provides a scaffold that smaller Western states cannot replicate alone.

Let’s not be naïve. Washington looks out for Washington. The 2003 invasion of Iraq wasn’t about European security. It destabilised the Middle East, radicalised many, and led to terrorist attacks across the West, including in Madrid, London, and Paris. American actions abroad often ignore allied consequences. This is a rational criticism.

However, what is the alternative? A world run by China, Russia, or Iran would not consider Western interests at all. China’s treatment of Uyghurs and suppression of Hong Kong speak for themselves. Russia’s expansionism and information warfare are destabilising forces. So even if America only inadvertently benefits the West, that is still preferable to direct antagonism from authoritarian blocs. British and European security thrives under American inertia.

The Case of Norway and the Fragile Periphery

Small nations like Norway, Iceland, Estonia, and even Switzerland flourish partly because they do not have to maintain large militaries. Norway spends just 1.5% of GDP on defense. It can afford lavish social welfare because someone else guards the sea lanes.

It’s plausible that these nations could survive even without the American umbrella—by making deals with new global powers like China, India, or a post-Putin Russia. They might retain prosperity via neutrality and diplomacy.

This is the most valid critique and worth conceding. Yes, socialist utopias could survive. But they would be forced into realpolitik negotiations. They’d lose moral leverage and ideological clarity. Economic prosperity would depend on staying silent about Tibet, Chechnya, or Iranian executions. Cultural integrity would be diluted by dependence on authoritarian benefactors.

Conclusion: A Necessary Empire

American hegemony is not just an abstract concept. It is the scaffolding upon which modern life, particularly in the West, has been built. It is a system flawed by excess, greed, and arrogance. But history teaches us that power vacuums are filled not by noble democrats—but by tyrants, generals, and opportunists. From a British perspective, supporting the American-led world order is not about blind loyalty. It’s about choosing the least destructive steward of global affairs. The multipolar world is coming regardless—but while it does, it is in our interest to keep the Empire standing a little longer. Not out of reverence. Out of necessity.